The FairShare Model: Chapter Eleven

Karl M. Sjogren

2015-07-03

Chapter 11: Valuation Concepts

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Send comments to karl@fairsharemodel.com

Preview

- Foreword

- Points to bear in mind

- What is the Value of an Idea?

- Startup Valuation Technology-Illustrated

- Valuation is a Challenge for Established Companies

- Valuation is a Challenge for Wall Street

- Valuation is a Challenge for VC and PE investors

- Valuation of Sustainable Companies

- What's the Harm of Getting Valuation Wrong?

- What's the Overall Harm of Getting Valuation Wrong?

- Why is a Valuation Necessary?

- Onward

Foreword

How might one think about valuation? How do the smartest guys in the room think about it? How might supporters of sustainable communities view the matter? What's the harm of getting it wrong? Why does a company need to have a valuation?

Points to bear in mind

- Valuation is price; price is not necessarily worth.

- A valuation may be seem reasonable in theory, but if no one is prepared pay that amount to buy the company outright, the value is speculative. Plus, what seems reasonable in a hot market looks untenable as it cools.

- A company's valuation is set whenever shares of its stock are sold by the company or by shareholders.

- In a private offering where there is a lead investor, the valuation is set via a negotiation between that investor and the issuer. If there is no lead investor, it is set by the company-a take it or leave it proposition.

- In a brokered public offering, the valuation is determined by the broker-dealer and issuer.

- In a direct public offering (no broker-dealer), the valuation is set by the issuer.

- In an acquisition, the valuation is set by negotiation between the seller and buyer (the acquiring company.)

What is the Value of an Idea?

Entrepreneurs differ on how much time, thought and effort they have put into getting the idea ready-to-go without being (fairly) paid-the "sweat equity." Typically, the value of an early stage company rests heavily on an idea and its perceived potential. So, what is the value of an idea?

Entrepreneurs and their friends and family are most likely to have the highest assessment. Savvy investors, I think, will smile at Derek Sivers' thoughts on this subject, which are below. On his website (www.sivers.org) he says "I'm a musician, programmer, writer, entrepreneur, and student - though not in that order. I'm fascinated with the usable psychology of self-improvement, communication, business, philosophy, and cross-cultural relativism. I love seeing a different point of view."

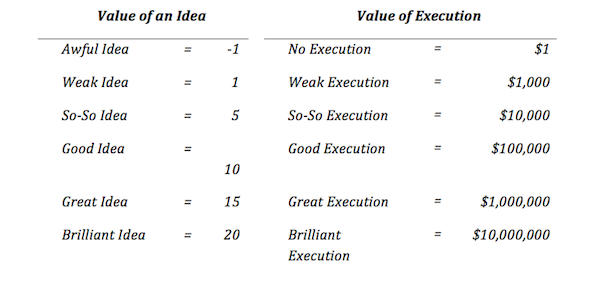

Ideas are just a multiplier of execution

By Derik Sivers

It's so funny when I hear people being so protective of ideas. (People who want me to sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement to tell me the simplest idea.)

To me, ideas are worth nothing unless executed. They are just a multiplier. Execution is worth millions. Explanation:

To make a business, you need to multiply the two.

The most brilliant idea, with no execution, is worth $20.

The most brilliant idea takes great execution to be worth $20,000,000.

That's why I don't want to hear people's ideas.

I'm not interested until I see their execution.

Most people, I suspect, would agree with Sivers. But, bear in mind, a conventional capital structure requires that a valuation be set on future performance anytime an equity financing takes place.

Can one reconcile his sentiment with a conventional capital structure? Sure! So long as it involves a private company; VCs routinely do it when they invest in a private company via deal terms. If it's a public offering to unaccredited investors, the answer is "no", which creates the opportunity, indeed, the need, for the Fairshare Model.

Startup Valuation Technology-Illustrated

Time magazine annually selects a Person of the Year, the person who had the most significance impact that year. The first, in 1927, was Charles Lindbergh. In 1938, it was Adolf Hitler. Joseph Stalin made it twice, in 1939 and 1942. So did George Marshall, first in 1943 as U.S. Army Chief of Staff and then in 1947 as Secretary of State and progenitor of the Marshall Plan to rebuild war-torn Europe. In 1982, remarkably, Time broke its tradition by naming a non-person, the personal computer, Person of the Year. It signaled that technology was poised to powerfully alter everyday life, the economy and more.

In the 1980s, the technology boom that had taken root in the Santa Clara Valley area at the south of the San Francisco Bay inspired a name to capture the phenomenon, "Silicon Valley." Publications sprang up that shed light on startup financing and culture. The emerging tech-cultural fusion created the ferment that allowed Wired magazine to launch in 1993. Less known nowadays is Upside, a magazine "for Silicon Valley about Silicon Valley" that started in 1989. That's because it went upside down in 2002, a casualty of the precipitous drop in advertising revenue that followed the dotcom and telecom bust.

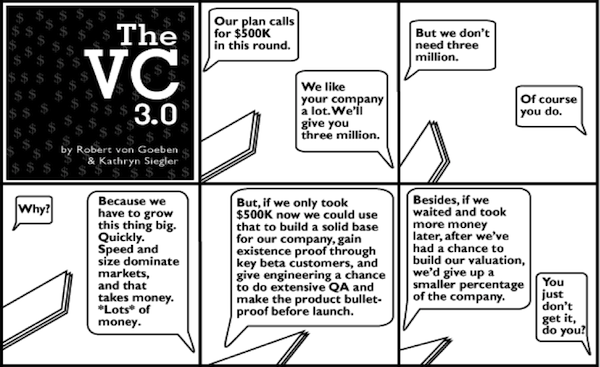

A regular feature in Upside was a cartoon strip called The VC that satirized issues related to the venture capital industry, which was growing rapidly. It was the creation of then-venture capitalist Robert von Goeben and artist Kathryn Siegler. They archive some of their strips at www.thevc.com. Here's one to give you the flavor of its humor.

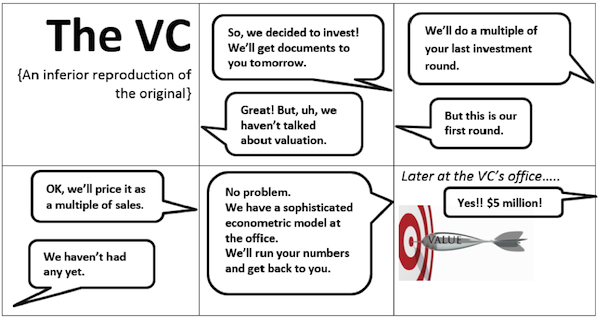

Remember, this was the dawn of the Internet Era. At the time, venture capitalists had concerns about mounting pre-money valuations for unproven companies that looked hot-they were moving from about $2 million to $5 million for a first round VC investment. The 2013 equivalent was $9.4 million. [1] The VC website does not have my favorite strip. It was on the subject of valuation, so, with apologies to von Goeben and Sieglar, I offer this version of what I remember.

The joke was that professional investors, these Masters of the Universe, really didn't have an objective way to evaluate valuation. Rules-of-thumb that had been applied for years by the old guard were being stretched by "new wave" VCs willing to accept valuations that were 2X higher or more. And, it was paying off for them because the IPO valuations were climbing on Wall Street.

Bill Reichert, managing director of Garage Technology Ventures tells the story about how he became a Silicon Valley software entrepreneur right out of graduate school in the 1980s. For reasons that mystified him at the time, VCs gave his team the capital they needed to launch a software company. It met with success and was eventually acquired. The same thing happened again. And then again. As an entrepreneur, he assumed that VCs had insight and techniques into how to value an early stage company. So, in the late 1990s, as he prepared to join their ranks by heading up Garage, he asked VCs he knew well, "What's the secret?"

He was told that the secret is that there is no secret. That VCs fund a deal because they fall in love. They fall in love with the company's market, its technology and its team. And, they feel, if they love the potential, others will come to love it too.

In other words, the valuation reflected emotion much more than a "sophisticated econometric model back at the office".

Valuation is a Challenge for Established Companies

Chew on this. The book, The Art of M&A is a "joint effort of Stanley Foster Reed, the founder of Mergers & Acquisitions magazine and Lane Edison, a law firm well known for its merger, acquisition and leveraged buyout transactions."

The authors report that executives at established companies struggle with their valuation, relative to that of an enterprise they want to acquire, even though there is an abundance of reliable data to evaluate. They open their "Valuation and Pricing" chapter this way:

No factor counts more than price in closing a transaction. Yet very few operating executives have any notion as to how much their or anyone else's companies are worth except from the stock tables. Very few know how to go about answering that question when they buy or sell. [2]

The Art of M&A is about legal and financial matters that arise in acquisitions of established companies, private and public. It's not about startups. But remember, a company's valuation for any round of financing is, presumptively, the price to buy the entire company. It's also the representation of worth that a company makes when it proposes terms for an investment. A single, large investor may well have a price in mind that is quite different from the valuation being offered to a group of smaller investors. Is it credible that anyone would pay the valuation price…now? If it is not-and incredible valuations are increasingly common-those who invest are less likely earn an attractive return. Whether a company is selling a slice of ownership or its entire self, valuation is important. And, if executives at large companies have a weak hold on valuation, it is unsurprising that others do as well.

An established company has years of revenue and earnings history. It has soft assets such as customers, a brand, know-how and other intellectual property that support products/services with demonstrated appeal. It has hard assets such as receivables, inventory and equipment. Taken as a whole, a due diligence review of this information will show where the company has been and provide a foundation for where it could go. An established company also has competitors who may value the company more highly than a financial investor because acquiring it allows them to add customers, reduce costs by consolidating operations, raise prices, etc.

A venture-stage company has few of these elements. Indeed, they often pursue new markets, so there is risk that the market for their product will not develop the way they expect or that competitors will outshine them. Whiz-bang technology can change the calculus, but only if the product is delivered in a timely way and is as impressive to customers as imagined. Compared to an established company, a venture stage company has a higher risk that its early customers will stop buying. Past success may be a poor predictor of future market demand.

If accomplished executives have difficulty assessing how to value a company with a developed business, you can expect that executives in venture-stage companies struggle even more to come up with a valuation for their start-up. You can also be sure that angel investors and professional investors have trouble too.

If you are less-than-confident about valuation issues, you have lots of company!

Valuation is a Challenge for Wall Street

How about companies that are not involved in an acquisition transaction? Is there an intrinsic value to a publicly traded stock? Finding an answer has been the Holy Grail of financial market theory development, the effort to credibly and consistently explain what is known or observed.

In his 1992 book, Capital Ideas: The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street, the late Peter L. Bernstein comprehensively examines the evolution of theories of how capital markets work. He says the idea of time value of money was well understood by the 1930s and that it led to the development of the dividend discount model as a way to evaluate the true value of a stock. The formula assumes that a stock's value come from its future dividend stream, discounted at a rate that reflects the time value of money and the risk associated with it. It is analytically sound. It is also intuitive that the value of an investment is derived from the income that it produces. The problem was that it doesn't explain prices

Columbia University's Benjamin Graham believed the difficulties of the Dividend Discount Model were insurmountable. [3] Although he believed that investors should base their decisions on the intrinsic value of a security, he felt it was "an elusive concept." In the seminal 1934 book Security Analysis, Graham and David Dodd used an analogy to suggest that an approximate measure of intrinsic value was good enough.

Graham and Dodd pointed out that "inspection [can reveal] whether a woman is old enough to vote without knowing her age, or that a man is heavier than he should be without knowing his exact weight." They defined intrinsic value as "that value justified by the facts, e.g., the assets, earnings, dividends, definite prospects." [4]

To establish an approximate measure of intrinsic value, many rely on fundamental analysis-a review of financial statements and models. When an established company is evaluated, much attention is on what its financial statements show. However, when the subject is a venture-stage company, the focus is on the projections because historic financial statements yield little insight into future value. This is especially so when the company intends to create a new market or there is high risk. One can only hope that the projection model is well thought out, considers the key drivers to success, has prudent assumptions and no computational or logic errors.

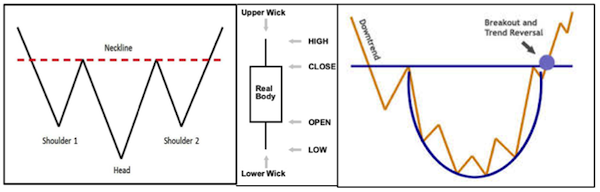

Another way Wall Street assesses value is a form of gestalt known as technical analysis. It relies on trend charts to discern if the current stock price appears too high, too low or just right. Like readers of tea leaves, technical analysts look for "heads and shoulders", "candlesticks" and "cup and handles", etc.

They also compare the price-earnings ratio to what it has been and to comparable companies. Technical analysis focuses on price trends, not the underlying worth of the asset.

As venture-stage company valuations were fueled by the bull market of the 1990s, Wall Street analysts evaluated them based on a multiple of "eyeballs"-Internet users who visited a website. The ability to attract traffic meant that the stock was worth more, based on the presumption that revenue and profit would follow. This line of thought lead a leading analyst in the bubble to opine that dotcom valuations could be rationalized as a multiple of marketing expense. Internet companies that had the highest marketing expense should be valued higher than competitors that were not spending so aggressively.

So, keep a standard for intrinsic value in mind as we proceed. On the one hand, it makes sense that there is one. Theoretically, if market participants had equal access to information, knowledge and the skill to exercise it, there would be agreement on what it is-and-variation in price would be based on new information. On the other hand, it is apparently impossible to establish in reality because intrinsic value is derived from expectations about the future, which is difficult to get consensus on. Besides, no one has demonstrated the ability to be reliably right.

Thus, if one is intent on building wealth via the public capital markets, two paths present themselves. The bright path involves vision, the ability to assess risk well, hard work, discipline, luck and fortunate timing. No one gets this reliably right, so, diversification is prudent. And, one's ability maximize diversification within a portfolio of a set size is to buy in at an attractive valuation. The dark path, of course, relies on gamed systems, inside information, manipulation of perception, deception and/or cheating.

Valuation is a Challenge for VC and PE investors

Venture capitalists (and their cousins, private equity funds) are the savviest investors around when it comes to valuation of a venture stage company. They are smart, connected, focused and usually invest in market sectors that they have domain expertise in, including contacts to vet a company's concept, business model and management team. But, they have trouble with valuation too.

Nonetheless, a valuation must be set when there is an equity financing. VCs negotiate the lowest valuation they can without alienating the entrepreneurs that they want to attract. They will accept a higher-than-comfortable valuation in exchange for securing deal terms that protect their interests. Frankly, they rely more on the deal terms than the valuation to protect their interests. Put another way, to secure a deal, a VC will tell the entrepreneur "I'll give you your price if you give me my terms." In real estate, that expression reflects a way to bridge a valuation gap between buyer and seller. The buyer will agree to pay more than she feels the property is worth now provided that the seller offers to stretch out payments long enough to make that price acceptable. Such a deal minimizes the cash outlay the buyer must make when uncertainty is high about its future value. If the value doesn't rise enough, the buyer can walk away without losing much.

Some of the ways that economic deal terms can protect a VC from overpaying are:

- If the company is sold, a liquidation preference entitles the VC to get a multiple of its investment back before other shareholders share in the proceeds;

- An anti-dilution clause can retroactively adjust down the price paid by the VC if a subsequent investor buys in at a valuation that is lower than provided in the terms.

- Redemption rights require a company to buy back the VC's investment in a few years if there isn't an investor exit. If the issuer can't, the equity investment can convert to debt, enabling the VC to "foreclose" on the assets. To avoid this, a company may offer the VC more shares at little or no cost.

- Conversion rights can enable a share of the VC's preferred stock to convert into more than one share of common stock when the company has an IPO (i.e., the VC's ownership can increase without further investment).

In addition, the VC will seek terms related to corporate governance and control that enable it to "minimize risks, protect against any downside, and thereby amplify the upside." [5] Control of the board of directors enables the VC to replace management, set priorities and decide major business decisions.

The point is that as important as valuation is for any investor, VCs can give ground on it because they secure rights that retroactively reset the deal if the performance fails to meet expectations. For that reason, it is more accurate to say that they negotiate the appearance of a valuation when they invest, not the actual valuation.

The illusory quality of a VC valuation is reported on in a March 2015 Bloomberg article titled The Fuzzy, Insane Math That's Creating So Many Billion-Dollar Tech Companies: Startups achieve astronomical valuations in exchange for protecting new investors, which is excerpted below. [Bold added for emphasis]

Snapchat, the photo-messaging app raising cash at a $15 billion valuation, probably isn't actually worth more than Clorox or Campbell Soup. So where did investors come up with that enormous headline number?

Here's the secret to how Silicon Valley calculates the value of its hottest companies: The numbers are sort of made-up. For the most mature startups, investors agree to grant higher valuations, which help the companies with recruitment and building credibility, in exchange for guarantees that they'll get their money back first if the company goes public or sells. They can also negotiate to receive additional free shares if a subsequent round's valuation is less favorable. Interviews with more than a dozen founders, venture capitalists, and the attorneys who draw up investment contracts reveal the most common financial provisions used in private-market technology deals today.

The backroom agreements are becoming more common as tech companies stay private longer, according to the interviews and financial documents obtained by Bloomberg Business. The practice obfuscates the meaning of a valuation, which can become dangerous down the road because private investors aren't taking the same risks a public-market shareholder would.

Some VCs defend the practice by saying valuations are just a placeholder number, part of an equation fueled by other, more important factors. Those can include market share, growth projections, and a founder's ego. The number is typically set by the company and negotiated alongside various provisions designed to protect a new backer's money. That often comes at the expense of employee shareholders and earlier investors, whose holdings are diluted to make room for new entrants.

"These big numbers almost don't matter," says Randy Komisar, a partner at venture firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. "Those numbers are just a middling shot at a valuation, and then it's adjusted later" through various legal techniques, if an earlier valuation was too high, he says.

A founder often starts off with a number in mind, based on the startup's last valuation, the valuations of competitors, and, for good measure, the valuation of the company's neighbor down the street. It can become a sort of arms race.

Startups [have] all sorts of provisions [in their financing documents] that reward investors for accepting these mega-valuations. The practice is more regular and egregious in financing rounds for mature companies. Their capital requirements tend to be much larger, so they must turn to more sophisticated investment firms that demand these kinds of terms. Startups that are generous with these guarantees can garner much higher valuations. [6]

Valuation of Sustainable Companies

There is rising interest in a so-called sustainable economies and companies. There may not be a clear, practical definition of what constitutes a sustainable company, but it is clear that those that aspire to operate in this category rely on investors who are open to non-traditional perspectives on value. As a result, they will have a different perspective on valuation, one defined by a community of interests.

A middling shot at a valuation is likely to consider what the enterprise seeks to accomplish and how credible it is, not just its financial projections. The same can be said for companies with a mission that holds special appeal for other reasons. It could be one that focuses on a niche market, a particular geography, or a technology for special needs. It may involve soil conservation, medical devices, toll roads, products/services for schools, water treatment technology, movie projects or media companies that have doubtful commercial prospects.

Think about the types of enterprises that rely on philanthropy, grants and donations to provide the capital they need. If they tap into the equity markets-replace contributions with equity-they will face a valuation challenge too. The figure will reflect the value of the business and its mission.

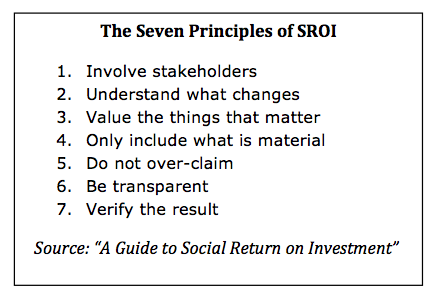

Ideas about how to define and apply alternative measures of value are more developed than many recognize. For instance, the United Kingdom government has an impressive publication, A Guide to Social Return on Investment (SROI), that explores how to determine a SROI for investors. [7] It identifies six stages to follow in order to establish a community-centric valuation:

- Establishing scope and identifying stakeholders

- Mapping outcomes

- Evidencing outcomes and giving them a value

- Establishing impact

- Calculating the SROI

- Reporting, using and embedding

The Fairshare Model holds promise for sustainable companies that want to raise capital using a public offering because it provides flexibility in defining value and performance.

What's the Micro-Economic Harm from Getting Valuation Wrong?

So, valuation is important but it is hard to know what it should be, no matter if the company is established or a start-up. What is the harm of accepting one that is "too high?" From an investor perspective, clearly, it increases the likelihood that money will be lost or less will be made than could have been.

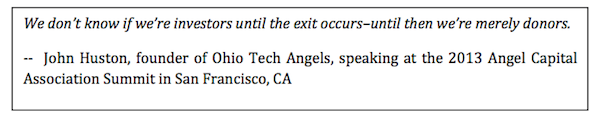

It is less obvious that entrepreneurs face challenges when they raise capital at an excessive valuation, as angel investor John Huston describes in a video on the angel investor site, Gust.

If I think back over the greatest ideas I've seen that have gone 'splat' and were never really brought to market, it's because they fumbled the funding plan.

The most prevalent way they've done that is that they go out to raise the most money at the highest valuation and they take checks from 'mullet's', as we call them, who are just hobbyist angels who don't know what the current market valuation is, they don't know about terms and conditions. And if an inadequate amount of capital is raised to take out the risk to justify the valuation that they raised the money on.

By definition, the next round (of capital) is a 'down round'. If you are an angel investor who sees a deal or two a day, why would you look at a down round?

A down round occurs when a company raises capital at a lower valuation than the prior one (i.e., it was overvalued earlier or failed to perform as expected). When that happens, a company loses its shine in the eyes of its shareholders. The expectancy that management is capable diminishes, a perception that seeps into how new investors view the latest projections. Stock option plans may get re-priced, fostering a sense that employees can benefit where early investors cannot. Rumors of weakness will float in the community.

The term "down round" is associated with a private company. Earlier investors don't have the ability to sell their shares, so they are effectively strapped in for the ride. I suppose it could apply to a public company-one that raises new capital at less than the IPO valuation. But in a public company, investors can sell when they want to get off the ride.

Regardless of whether a company is private or public, Huston's point applies: a business that otherwise has an upside introduces a downside when either the company or its investors are not valuation aware and savvy.

What's the Macro-Economic Harm from Getting Valuation Wrong?

There is a broader harm that comes from valuation unawareness-it fuels asset valuation bubbles that wreak havoc. There is a long history of these occurring, as explained in the PBS Nova program, Mind Over Money; Can markets be rational when humans aren't? Here is an excerpt from the program. [8]

The first financial bubble involved something highly unlikely.

JUSTIN FOX (Harvard Business Review): In the 1630s, in the Netherlands, people were buying and selling Tulip bulbs...complete, mass insanity in Holland, for a couple of years there, where hundreds of people, artisans, would leave their workshops and set up business as "florists," they called themselves, although, for the most part, what they really were were tulip bulb traders. And it was a real financial market.

ROBERT SHILLER (Yale University): The price of tulips in Holland rose to such a level that the value of one tulip bulb would sometimes be that of an entire house.

NARRATOR: Over a three-year period, the price of tulip bulbs rose and rose, and then began to soar. By some accounts, almost half of all the money in the Dutch economy was caught up in trades involving tulips.

JUSTIN FOX: To a lot of historians, this is really the first example of a financial bubble, even though it was, basically, tulips.

ROBERT SHILLER: People were buying them, not primarily because they liked tulips, but they were buying them because they thought that the price was going up and they could resell them to someone else at a higher price.

NARRATOR: On February 5, 1637, the most expensive bulb in Holland failed to sell, and tulip investors panicked.

ROBERT SHILLER: Then it burst, because prices start falling. And then they're falling more, and then you start thinking, "You know, I remember I doubted that tulips could possibly be worth so much. Maybe I better get out fast." And then everyone starts dumping, and then it just drops.

NARRATOR: As the prices plunged, leading citizens found themselves bankrupt. Some historians estimate it took a generation for the Dutch economy to recover. There have been many bubbles and crashes since, but the most famous happened closer to home.

The year 1929 began with optimism. Stock prices had been rising for eight years, and in '29 they were soaring.

JUSTIN FOX: The 1920s was a great decade economically. The economy was booming, industry was booming, and toward the latter part of the decade, financial markets just sort of went from reflecting that boom to, kind of, creating it. It was just boom times all over. By the late 1920s, there was just this feeling of a new era.

NARRATOR: Observers described feverish emotions, as thousands of investors paid ever-higher prices for stocks.

ROBERT SHILLER: In the so-called "roaring '20s" the stock market went through an enormous bubble; people thought it would never end.

NARRATOR: But then, on October 29th, prices suddenly dropped, and the mood turned to one of panic and fear. Over 9,000 American banks failed, wiping out the life savings of millions.

ROBERT SHILLER: It led to a depression that lasted over 10 years.

More recently, there was the dotcom and telecom bubbles that burst in 1999-2000. Technology promised to transform many facets of life. Investors saw young companies coming into the stock market that had questionable prospects…and they went up in price anyway. The accelerant was that many public investors were unfamiliar with valuation and how to evaluate it.

Now, valuation awareness does not, in and of itself, prevent bubbles. Investors may be valuation aware but be unsure about how the evaluate a valuation. Or, they may decide that FOMO-Fear Of Missing Out-trumps prudence. When enough people share this sense, bubbles grow, until they bust. It's a cycle we've seen for generations in securities and real estate.

Cheerleaders are the handmaidens of bubbles because they conjure up ways to rationalize bubbles. During the 1990s the number of visitors or "eyeballs" a website attracted drove valuations. Highly regarded Wall Street analysts argued that companies that spent the most on marketing should be the more highly valued. It was crazy idea but one that explained what was happening in the market. At the time, the CEO at a small public company told me that he expected to attract investors at a high valuation by showing he would spend heavily on marketing-he was later fired.

Valuations of venture-backed startups are blossoming nowadays and cheerleaders are evident again. For example, in an August 2014 opinion article in the Wall Street Journal, the CEO of a business valuation firm asserts that: [9]

- The majority of startups and small businesses are not overvalued.

- It is the startups that create new markets that can ask for larger premiums.

- We should do more to create new companies and not worry as much if the companies being created are overvalued or not. As a country, we should focus on helping them have better knowledge and access to capital.

Tellingly, this view is advanced by someone positioned to profit from rising valuations…a firm that charges companies to opine on what they are worth. The arguments made about eyeballs or marketing expense were made by analysts affiliated with the underwriters of the companies they rationalized high value for.

Strikingly, future performance is both presumed and deemed valuable enough to command a premium. Why? Because no one has done it before!

More provocative is the argument that we should not worry about whether companies are overvalued. Opposing perspectives come to mind when I contemplate this. On the positive side, an entrepreneurial culture thrives when capital is available on attractive terms and such a culture feeds an innovative economy. So, yes, we need to improve access to capital, as the writer suggest. On the negative side, yikes! Do we not learn from history? Are we destined to relive boom bust cycles?

Economist Hyman Minsky considered this question and concluded that financial markets are inherently vulnerable to them. Early in 2008, before the downturn was called the Great Recession, The New Yorker summarized Minsky's financial-instability hypothesis this way: [10]

[In the early 1980s,]when most economists were extolling the virtues of financial deregulation and innovation, a maverick named Hyman P. Minsky maintained a more negative view of Wall Street; in fact, he noted that bankers, traders, and other financiers periodically played the role of arsonists, setting the entire economy ablaze. Wall Street encouraged businesses and individuals to take on too much risk, he believed, generating ruinous boom-and-bust cycles.

Many of Minsky's colleagues regarded his "financial-instability hypothesis," which he first developed in the nineteen-sixties, as radical, if not crackpot. There are basically five stages in Minsky's model of the credit cycle: displacement, boom, euphoria, profit taking, and panic. A displacement occurs when investors get excited about something-an invention, such as the Internet, or a war, or an abrupt change of economic policy.

As a boom leads to euphoria, Minsky said, banks and other commercial lenders extend credit to ever more dubious borrowers, often creating new financial instruments to do the job. During the nineteen-eighties, junk bonds played that role. More recently, it was the securitization of mortgages, which enabled banks to provide home loans without worrying if they would ever be repaid. Then, at the top of the market, some smart traders start to cash in their profits. The onset of panic is usually heralded by a dramatic effect.

Stock manias could be included in the article. Contrary to what the CEO wrote in his WSJ Op-Ed piece, there is reason to believe that venture-stage companies are overvalued, and, that the combination of cheerleaders, a lack of valuation savvy and FOMO are a recipe for a boom bust cycle.

This tempers my enthusiasm for equity crowdfunding. I'm not bothered that investors will lose money, I bothered that they will lack the ability to make bets that have a reasonable chance of paying off. I look at venture stage investing as a game of roulette. The more numbers you place bets on, the more likely it is that you will have a winner. It is easy to lose one's head when betting; one is less likely to lose it when the chips are inexpensive (i.e., valuations are low).

Simply put, the overall harm of getting valuation wrong is that it encourages speculation that leads to boom bust cycles, something that is bad for an economy. Speculation that supports adventurism-more bets on the table-is desirable because it supports innovation. The trick is to simultaneously encourage adventurism and realistic valuations.

I am enthusiastic about equity crowdfunding provided that public investors have the opportunity to get the type of deal a VC gets.

Why is a Valuation Necessary?

Why is it necessary to set a valuation? Why can't people just provide the money a company it needs and compensate employees for doing a good job? Such questions may come to mind to readers who are unfamiliar with capital structures.

The answer rests on what the people want in exchange providing the organization with the capital it needs to operate. If they want an ownership interest, a valuation is needed to establish what it is relative to earlier providers of capital and to those who provide ideas and labor. If no ownership interest is required, the organization will simply ask those providing the capital for a donation. If it is registered as a not-for-profit company with the Internal Revenue Service, those who donate can write off the contribution from their taxable income in the year they send the money. If it is registered as a for-profit company with the IRS, those who provide the money must wait until they sell their ownership at a loss or the entity liquidates to write off their "contribution."

An ownership interest enables contributors of resources to have something to sell to others. Without one, as just noted, they are merely donors!

The ownership interests in the Fairshare Model have a valuation, however, it provides incentive for those who contribute ideas and labor to offer a low valuation because the price of future performance is separated from price of the capital raised to support it.

Thus, the Fairshare Model answers the question "Why is it necessary to set a valuation?" by decoupling the value for delivered performance from the value of future performance. Essentially, the providers of unproven ideas and undelivered labor say to the providers of capital "We don't know what the value of our prospects are, so we are willing to defer the matter until we deliver performance provided we feel assured that we will be appropriately rewarded."

Onward

Valuation is something that the smartest people in the room have trouble with, regardless of whether a company is a start-up or established. For this reason, Dear Reader, even though you may be a complete novice on valuation, there are two questions you can ask of anyone who is raising money for a company that will make you appear astute on the subject. The first is "what is the valuation?" and the second is "why does that make sense?"

Venture-stage companies are particularly difficult to value. Nonetheless, the beast otherwise known as a conventional capital structure demands a valuation of future performance. The Fairshare Model renders this issue unimportant. The question for financial professionals is, how will valuation theory change if the villagers-entrepreneurs and investors-realize that they don't have to feed the beast?

With these concepts in mind, we move onto how to calculate the valuation that a company has given itself.

[1] "Startup valuations keep rising", Dan Primack, Fortune, Jan. 16, 2014, http://fortune.com/2014/01/16/startup-valuations-keep-rising/

[2], The Art of M&A, Stanley Foster Reed (1989), Richard D. Irwin, Inc. ,page 63

[3] Graham is considered the father of "value investing" and his most famous student is billionaire Warren Buffet.

[4] Bernstein, Peter; Capital Ideas, Page 158

[5] Ramsinghani, Mahendra; "The Business of Venture Capital", John Wiley & Sons (2011), page 230

[6] "The Fuzzy, Insane Math That's Creating So Many Billion-Dollar Tech Companies", by Sarah Frier and Eric Newcomer, Bloomberg, Mar. 17, 2015 http://bloom.bg/1wV4oE7

[7] http://www.bond.org.uk/data/files/Cabinet_office_A_guide_to_Social_Return_on_Investment.pdf

[8] http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/mind-over-money.html

[9] "A Look At Startup Valuations Now and Then" by Michael Carter, Wall Street Journal, Aug. 29, 2014, http://blogs.wsj.com/accelerators/2014/08/29/michael-carter-a-look-at-startup-valuations-then-and-now/

[10] http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/02/04/the-minsky-moment

By Karl M. Sjogren *

Send comments to karl@fairsharemodel.com

Karl M. Sjogren *

Contact Karl Sjogren is based in Oakland, CA and can be contacted via email or telephone:

Karl@FairshareModel.com

Phone: (510) 682-8093

The Fairshare Model Website

A native of the Midwest, Karl Sjogren spent most of his adult life in the San Francisco Bay area as a consulting CFO for companies in transition—often in a start-up or turnaround phase. Between 1997 and 2001, Karl was CEO and co-founder of Fairshare, Inc, a frontrunner for the concept of equity crowdfunding. Before it went under in the wake of the dotcom and telecom busts, Fairshare had 16,000 opt-in members. Given the rising interest in equity crowdfunding and changes in securities regulation ushered in by the JOBS Act, Karl decided to write a book about the capital structure that Fairshare sought to promote….”The Fairshare Model”. He hopes to have his book out in Spring 2015. Meanwhile, he is posting chapters on his website www.fairsharemodel.com to crowdvet the material.

Material in this work is for general educational purposes only, and should not be construed as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances, and reflects personal views of the authors and not necessarily those of their firm or any of its clients. For legal advice, please consult your personal lawyer or other appropriate professional. Reproduced with permission from Karl M. Sjogren. This work reflects the law at the time of writing.